Desplácese hacia abajo para leer la traducción al español de esta historia.

I recently led a workshop and artist talk titled “Woodblock Prints and Medicine: Sugar and Tobacco in the Caribbean” based on my research, sourcing materials from UCSF’s Industry Documents Library (IDL), IDL’s Sugar Collection, and Japanese Woodblock Print Collection. These long-standing plantations harvested an economy that brought industry, and advancements in manufacturing and medicine, built on a system of slavery and exploitation. The documents exposed the unrelenting treatment of the Puerto Rican people and the growth of the massive pharmaceutical industry at the hands of colonial powers. Showing these stories through Ukiyo-e style woodblock prints supports the idea that our bodies are floating worlds, with each of our systems and organs characterized as a person or scene. These depictions draw connections within the human body regarding health, trauma, and diseases. The following images are attributions based on the original Japanese woodblock prints seen above each of my renderings.

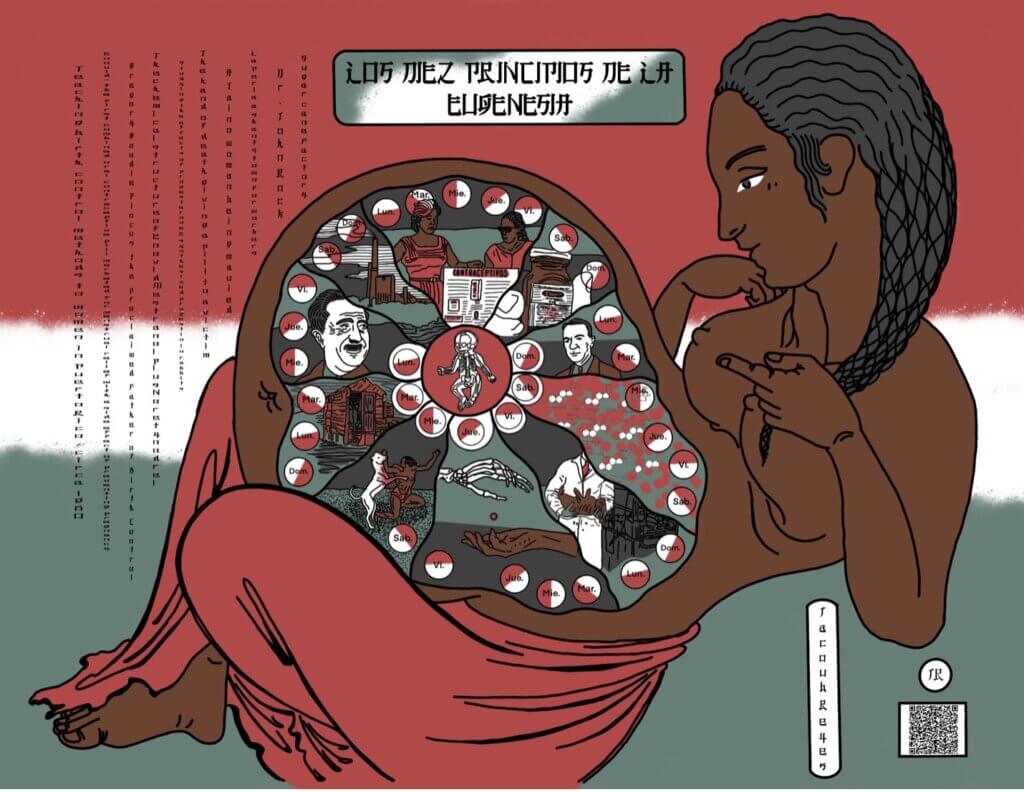

Los diez principios de la eugenesia

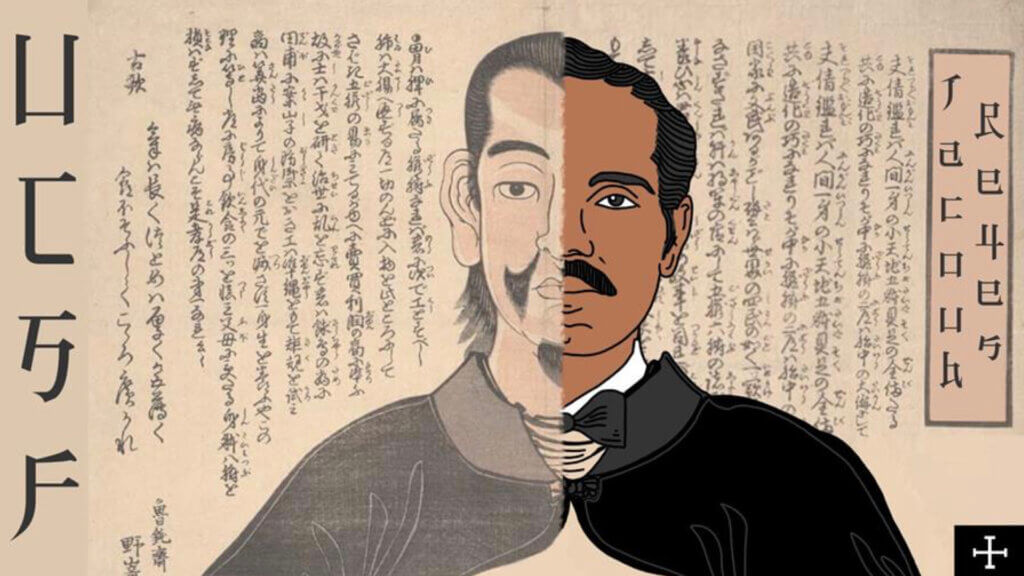

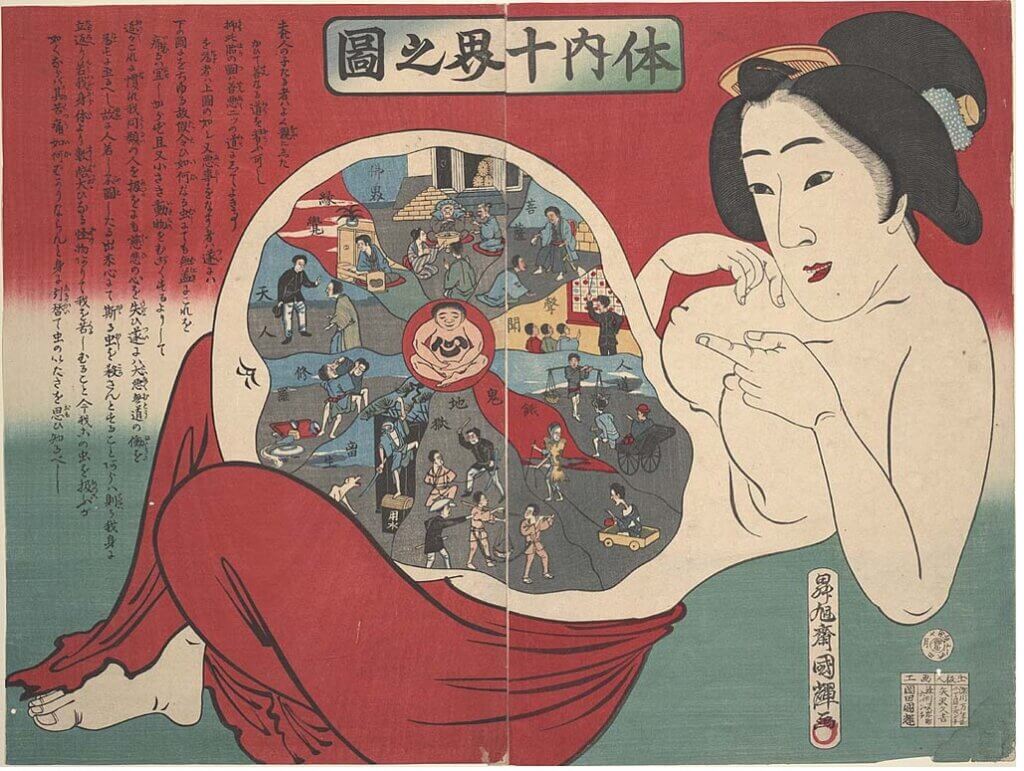

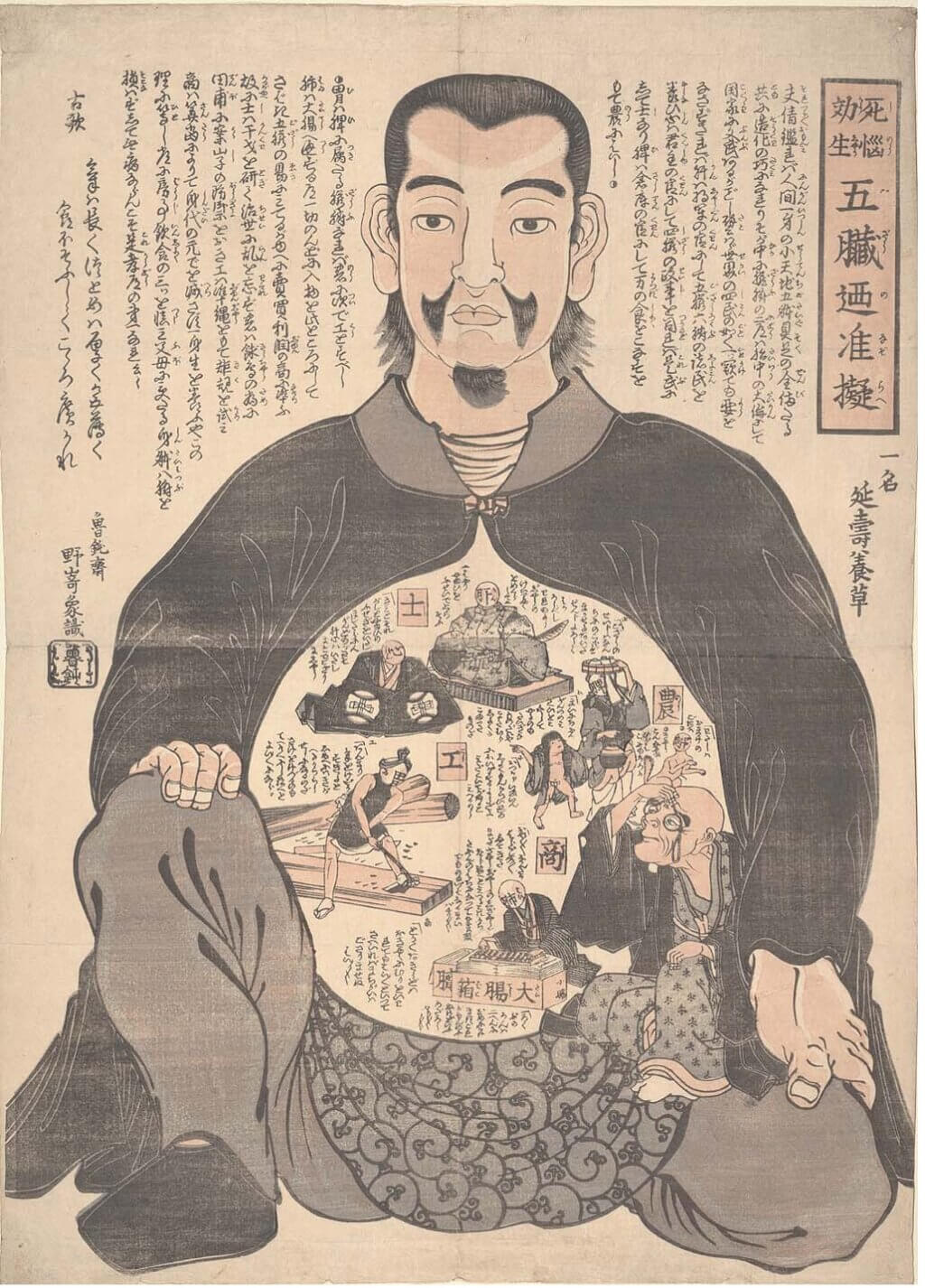

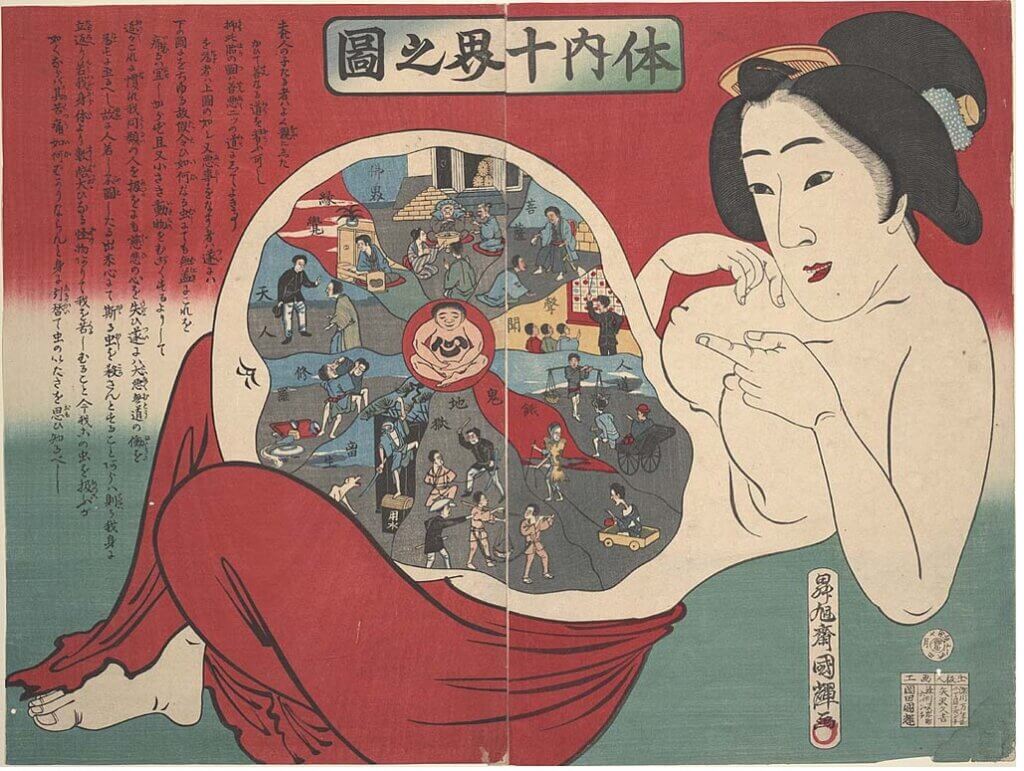

The first image, Los diez principios de la eugenesia is based on Kuniteru Utagawa III’s, Tainai jukkai no zu (Ten realms within the body), 1885.

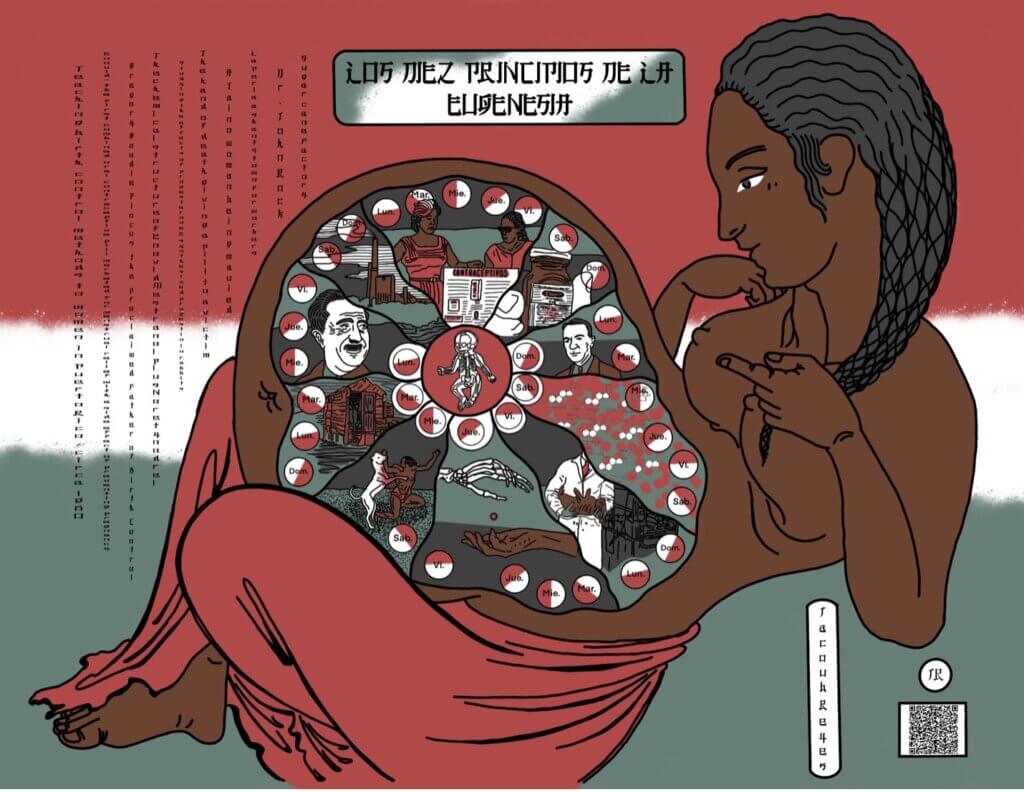

The following image shows a Taino woman pointing at her abdomen. Within this space is a contraceptive pill pack surrounding the experimental birth control history segments.

An explanation of the internal world of the woman, starting from the top-center and moving clockwise, is listed below:

- Teaching birth control methods to other women in Puerto Rico circa 1960.

- Enovid, the first combined oral contraceptive pill marketed for menstrual relief with a side effect of preventing pregnancy.

- Dr. John Rock, a scientist recruited to help Dr. Gregory Pincus investigate the clinical use of progesterone to prevent ovulation (Pincus, 1968).

- The chemical structure of Enovid, Mestranol, plus Noretynodrel.

- Injections of the hormone progesterone prevented ovulation in rabbits used in Gregory Pincus and Dr. M.C. Chang’s experiments. Progesterone prepares a fertilized egg for implantation into the uterus and shuts down the ovaries so no more eggs are released. There were many reasons scientists had not injected humans, some of them being there were too many risks, and progesterone was very expensive (Roberts, 2015).

- The hand of death transferring a pill to an unsuspecting recipient.

- A dog mauls a Taino woman during a mass attack from colonial forces.

- La Perla, a shanty town for enslaved people, servants, farmers, and later workers, is located by a cemetery.

- Dr. Gregory “Goodie” Pincus, the proclaimed “Father of Birth Control.”

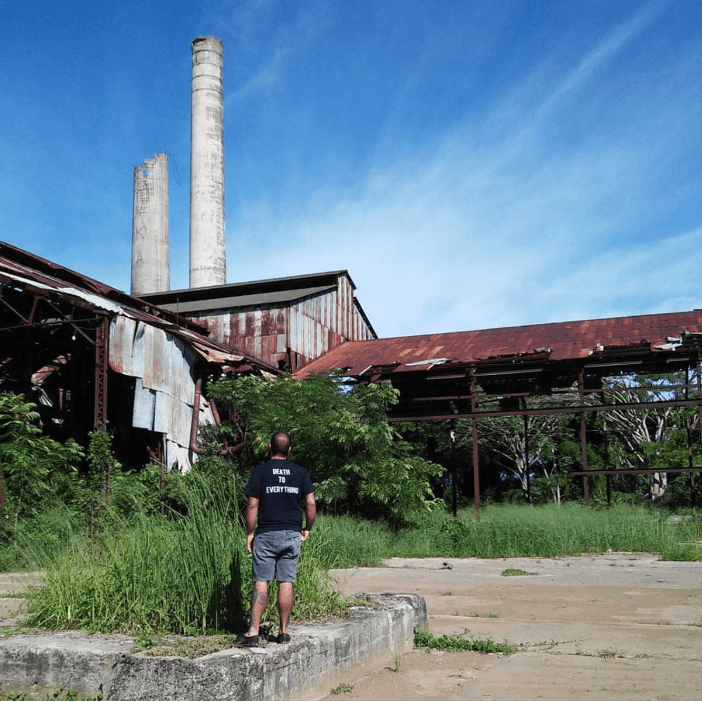

- A sugarcane factory signifying the end of the agrarian system and the initiation of Operation Bootstrap.

A brief colonial history in Puerto Rico

Women and children have historically been the targets of unethical practices. These vulnerable populations directly reflect the trauma brought forth by the sugar and tobacco industries, which paved the way for the now pharmaceutical sector (Supreme Court, 1995). These industries have affected the island’s population through diabetes, addiction, and death.

Spain started the sugar plantation system only two decades after they colonized Puerto Rico. From 1493 to 1898, as many as 789 sugar plantations had land dedicated to commercial agriculture across the island (Malone & Morton, 2021). The Treaty of Paris of 1898 forced Spain to cede Puerto Rico to the U.S., which allowed the U.S. to appoint a civilian governor under the Foraker Act, Charles Herbert Allen, and placed the island under military rule. Allen was a corrupt businessman with no background in governmental practices and policies. He slashed operating expenses on the island, refusing to use the budget surplus to make essential infrastructure and education investments. With the extra funds, he instead re-directed them to no-bid contracts for U.S. businessmen, building roads at double the cost, railroad subsidies for U.S.-owned sugar plantations (his father owned Otis Allen and Son, a lumber business that created wooden boxes and sold railroad ties, housing frames, and road building materials), and high salaries for U.S. bureaucrats in the island government (Allen & McKinley, 1901). He was also listed as one of the “Politicians in the Lumber and Timber Business in Puerto Rico” (Library of Congress). In the single year Allen was governor, he managed to appoint half of the offices in the government to visiting Americans (626 individuals), and nearly all the Executive Council were U.S. expatriates (Maldonado-Denis, 1972).

In 1901, Allen resigned as governor, fled to Wall Street, and joined the House of Morgan (J.P. Morgan & Co.) and the Guaranty Trust Company of New York as their vice president. In 1907 he created the world’s largest sugar syndicate in Puerto Rico, the American Sugar Refining Company (later the Sugar Trust). This Trust owned and controlled 98% of the sugar processing capacity in the United States. Allen’s political appointees in Puerto Rico provided him with land grants, tax subsidies, water rights, railroad easements, foreclosure sales, and favorable tariffs (Tovar et al., 1971). By 1930, Allen and his banking partners converted 45% of all arable land into sugar plantations. They owned the insular postal system, the entire coastal railroad, and the international seaport of San Juan. Today, the syndicate is known as Domino Sugar.

These forms of governmental nepotistic and unethical business models have continued ’til today in the form of massive tax breaks to large pharmaceutical companies (over $250 billion between 2017 and 2023). The U.S. government claims that creating a big pharmaceutical haven in Puerto Rico would create jobs and support communities. However, only roughly 7,000 jobs have been created, and many workers face low wages, inadequate benefits, and poor workplace safety. The exploitation model of the sugarcane plantations has synthesized itself into a new, addictive behemoth- the pharmaceutical industry of the American empire (Varona, 2022).

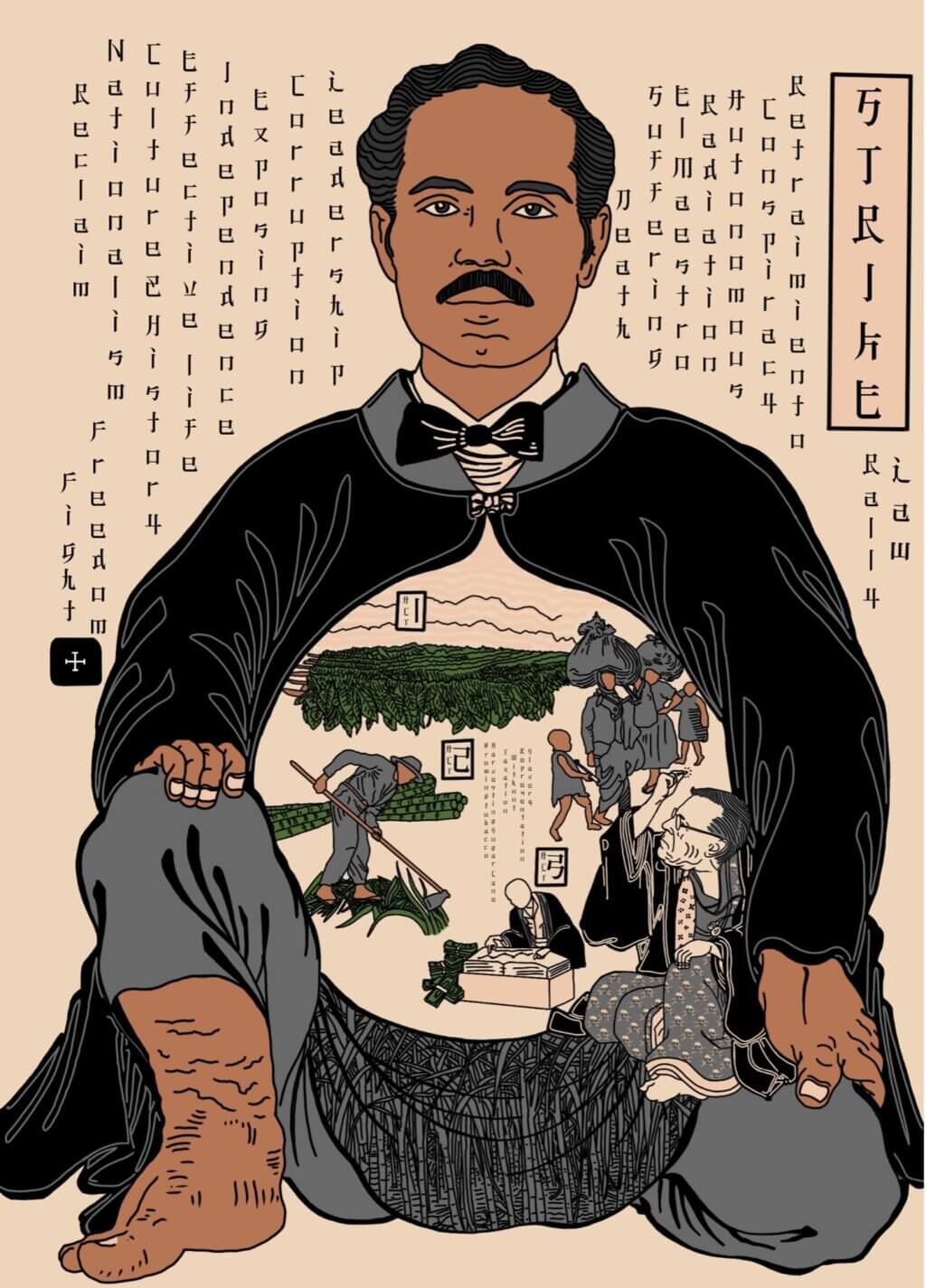

El maestro y la esperanza de una nación

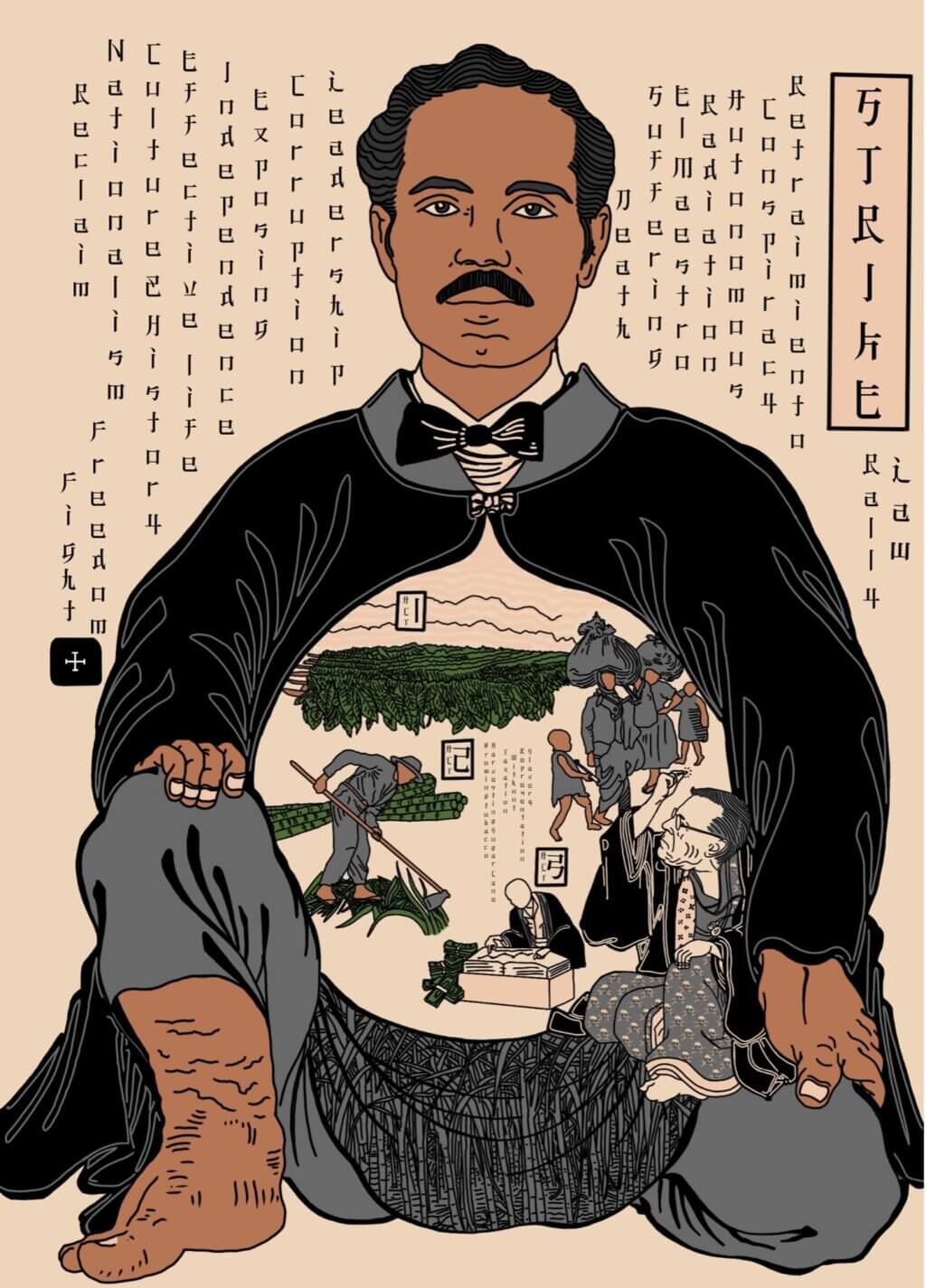

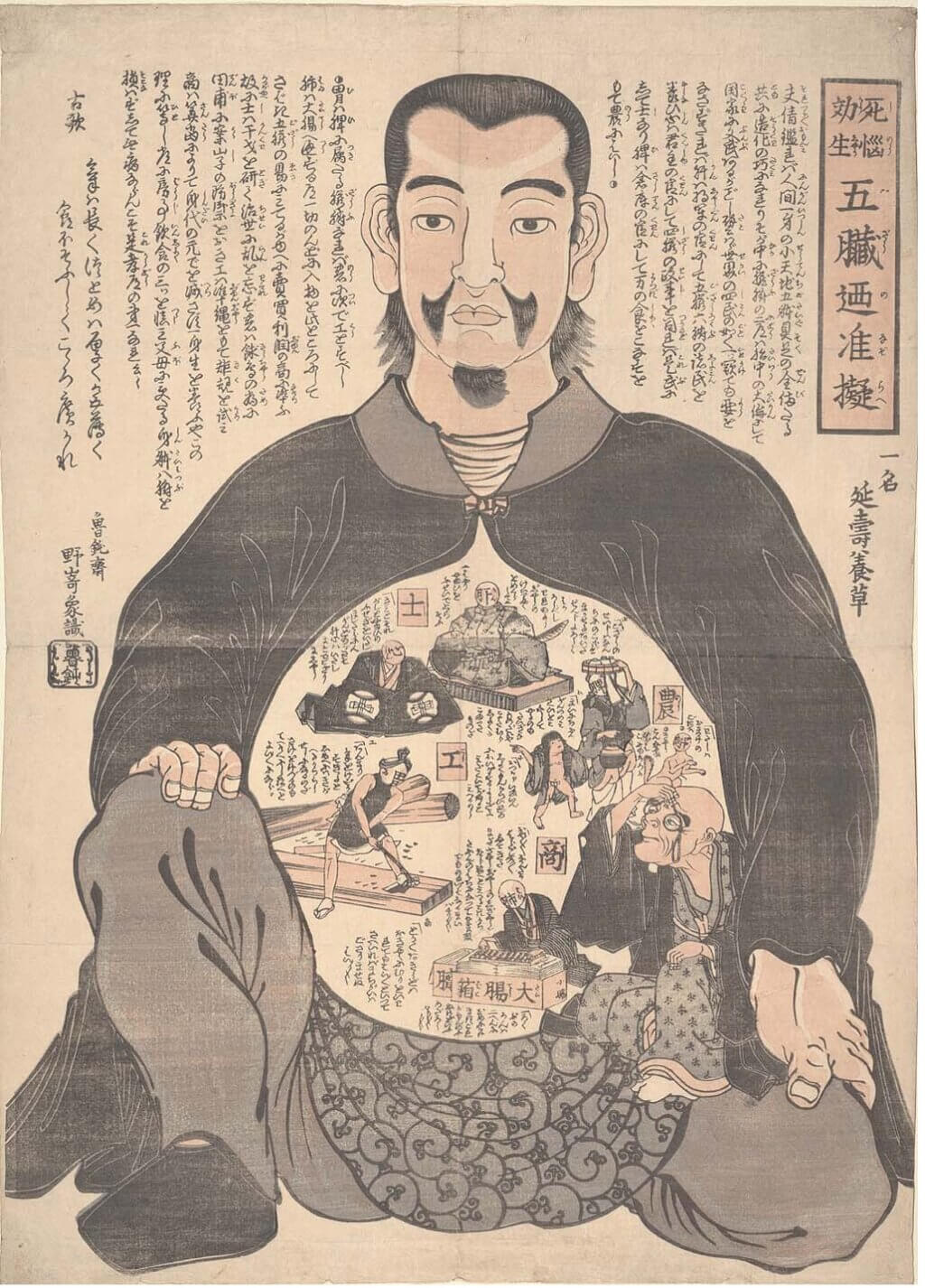

The second image, entitled El maestro y la esperanza de una nación is inspired by Nozoki Shōshiki Rodonsai’s, Shinō kōshō gozō no nazorae (Suffering, death, and effective life: metaphorical classifying organs according to 4 levels of social status, shinō kōs hō (samurai, farmer, artisan, merchant) from the late 19th century.

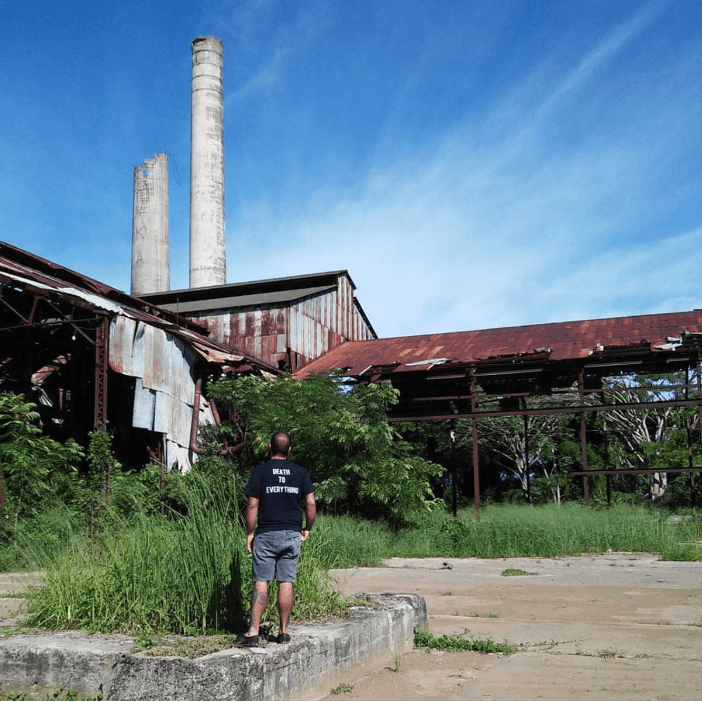

El maestro y la esperanza de una nación examines the various levels of social hierarchy in the Caribbean-European plantation system. The scenes in the stomach are encapsulated by a man known as Pedro Albizu Campos, a Puerto Rican attorney, social activist, and nationalist. He led an island-wide agricultural strike, with over 85 rallies in 1933 alone, which created awareness around the sugarcane, tobacco, needlework, and transportation industries. These rallies intended to raise sugarcane worker wages from $0.45 to $1.50 per 12-hour day (Villanueva, 2009). His efforts to teach and encourage others to fight for freedom and sovereignty led to 24-hour surveillance by FBI officials, a gag law, and 25 years of imprisonment which led to his eventual death by radiation experimentation, seen in his inflamed foot. These lethal doses of radiation caused welts, burns, and cerebral thrombosis.

Descriptions of the scenes can be seen below, starting from the top-center and moving clockwise.

- A large plantation of tobacco crops. To the right are enslaved people and indentured servants carrying cow manure in bags on their heads. Their children help with odds and ends.

- A worker cuts grass to ready the land for the next season of crops. Behind him lay large bundles of sugarcane.

- A plantation owner/ politician counts and tracks their profits as they sit beside a pile of money.

Cornelius P. Rhoads, an instructor of Pathology at Harvard and staff at Rockefeller University and Hospital, sits to the right of these scenes. He is draped in a skull-and-crossbones kimono, looking at a red pill, which represents his vehement support of contraceptives on the island, along with his six-month stint in 1932 injecting cancer cells into the Puerto Rican people. He also experimentally altered his subjects’ (or, as he would refer to them, “experimental animals”) diets to induce the conditions he researched instead of treating the ailments (Lederer, 2002). An excerpt from his letter follows: “They [Porto Ricans] are beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate, and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere. It makes you sick to inhabit the same island with them. They are even lower than Italians. What the island needs is not public health work but a tidal wave or something to totally exterminate the population. It might then be livable. I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off 8 and transplanting cancer into several more. The latter has not resulted in any fatalities so far… The matter of consideration for the patients’ welfare plays no role here — in fact, all physicians take delight in the abuse and torture of the unfortunate subjects” (Rosenthal, 2003). This letter was given to Pedro Albizu Campos, who distributed it worldwide to various media outlets. Albizu believed that Rhodes was part of a larger U.S. government plot to exterminate Puerto Ricans.

The Industry Documents Library and IDL’s Sugar Collection resources have added important context and supporting documentation to my research. Much of Puerto Rico’s history has been downplayed or covered up due to corrupt politicians and special interests. Utilizing the Japanese Woodblock Collection has also had an insightful impact on my project and process by creating approachable images for complex topics. The next workshop will cover traditional Japanese woodblock techniques using chisels, ink, and hand-printing. I will also touch on the technological aspects of this project and the works created through The Makers Lab at UCSF.

Works cited

Pincus, G. (1968). The control of fertility: Gregory Pincus. London, Academic Press.

Roberts, W. C. (2015). Facts and ideas from anywhere. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 28(3), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2015.11929297

Supreme Court. (1995). Report on Gender Discrimination in the Courts of Puerto Rico: Chapter 1: General Theoretical Framework. Puerto Rico. Special Judicial Commission to Investigate Gender Discrimination in the Courts.

Malone, S., & Morton J. PBS LearningMedia. (2021). Slavery and Sugar Cane Plantations in Puerto Rico | Finding Your Roots. PBS LearningMedia. Retrieved February 15, 2023, from https://florida.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/slavery-sugar-cane-plantations-puerto-rico-video/finding-your-roots-season-six/

Allen, C. H., & McKinley, W. (1901). First Annual Report of Charles H. Allen, governor of Porto Rico, covering the period from May 1, 1900, to May 1, 1901. respectfully submitted to Hon. William McKinley, president of the United States, through the Hon. John Hay, secretary of State. May 1, 1901.

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Allen, Charles Herbert. US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Retrieved February 19, 2023, from https://history.house.gov/People/Detail/8422?ret=True

Maldonado-Denis, M. (1972). pp. 70–76. In Puerto Rico: A socio-historic interpretation. essay, Vintage Books.

Tovar, F. R., & Rawlings, A. (1971). Albizu Campos: Puerto Rican revolutionary (pp. 122–144, 197–204). New York, NY: Plus Ultra Educational Publ.

Varona, J. L. (2022, August 19). Puerto Rico has a big-pharma problem. The Nation. Retrieved February 19, 2023, from https://www.thenation.com/article/economy/puerto-rico-big-pharma/#:~:text=Between%202017%20and%202023%2C%20Puerto,by%20using%20offshore%20tax%20havens

Villanueva, V. (2009). Colonial Memory and the Crime of Rhetoric: Pedro Albizu Campos. College English, 71(6), 630–638. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25653000

Lederer, S. E. (2002). “Porto ricochet”: Joking about germs, cancer, and race extermination in the 1930s. American Literary History, 14(4), 720–746. https://doi.org/10.1093/alh/14.4.720

Rosenthal, E. T. (2003). The Rhoads not given: The tainting of the Cornelius P…. : Oncology Times. LWW. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://journals.lww.com/oncology-times/Fulltext/2003/09100/The_Rhoads_Not_Given__The_Tainting_of_the.7.aspx

Puerto Rico y el Sistema Americano de Plantaciones

Recientemente dirigí un taller y una charla de artistas titulada “Grabados en madera y medicina: azúcar y tabaco en el Caribe” basado en mi investigación, obteniendo materiales de la Biblioteca de Documentos de las Industrias (IDL por sus siglas en inglés), (IDL) de la Colección de Azúcar y (IDL) de la Colección Japonesa de Grabados en Madera, de UCSF. Estas plantaciones de larga duración cosecharon una economía que trajo la industrialización y avances en la fabricación y la medicina, construida sobre un sistema de esclavitud y explotación. Los documentos expusieron el trato implacable al pueblo puertorriqueño y el crecimiento de la industria farmacéutica masiva a manos de los poderes coloniales. Mostrando estas historias a través de grabados en madera estilo Ukiyo-e respalda la idea de que nuestros cuerpos son mundos flotantes, con cada uno de nuestros sistemas y órganos caracterizados como una persona o escena. Estas representaciones trazan conexiones dentro del cuerpo humano con respecto a la salud, el trauma y las enfermedades. Las siguientes imágenes son atribuciones basadas en las xilografías japonesas originales que se ven arriba de cada una de mis representaciones.

Los diez principios de la eugenesia

La primera imagen, Los diez principios de la eugenesia, está basada en Tainai jukkai no zu (Diez reinos dentro del cuerpo), de Kuniteru Utagawa III, 1885.

La siguiente imagen muestra a una mujer taína señalando su abdomen. Dentro de este espacio hay un paquete de píldoras anticonceptivas que rodea los segmentos de la historia del control de la natalidad experimental.

Una explicación del mundo interno de la mujer, comenzando desde el centro superior y moviéndose en el sentido de las agujas del reloj, se enumera a continuación:

- Enseñando métodos anticonceptivos a otras mujeres en Puerto Rico alrededor de 1960.

- Enovid, la primera píldora anticonceptiva oral de comercialización combinada para el alivio menstrual con un efecto secundario de prevención del embarazo.

- Dr. John Rock, un científico contratado para ayudar al Dr. Gregory Pincus a investigar el uso clínico de la progesterona para prevenir la ovulación (Pincus, 1968).

- La estructura química de Enovid, Mestranol, más Noretynodrel.

- Las inyecciones de la hormona progesterona impidieron la ovulación en conejos utilizadas en los experimentos de Gregory Pincus y Dr. M.C. Chang. La progesterona prepara un óvulo fertilizado para su implantación en el útero y apaga los ovarios para que no se liberen más óvulos. Había muchas razones por las que los científicos no habían inyectado humanos, algunas de ellas porque había demasiados riesgos y la progesterona era muy cara (Roberts, 2015).

- La mano de la muerte transfiriendo una pastilla a un destinatario desprevenido.

- Un perro ataca a una mujer taína durante un ataque masivo de las fuerzas coloniales.

- La Perla, un barrio de chabolas para esclavos, sirvientes, agricultores y más tarde trabajadores, está ubicado junto a un cementerio.

- Dr. Gregory “Goodie” Pincus, el proclamado “Padre del control de la natalidad”.

- Una fábrica de caña de azúcar que significa el fin del sistema agrario y el inicio de la Operación Bootstrap.

Una breve historia colonial en Puerto Rico

Históricamente, las mujeres y los niños han sido objeto de prácticas poco éticas. Estas poblaciones vulnerables reflejan directamente el trauma provocado por las industrias azucarera y tabacalera, que allanaron el camino para el ahora sector farmacéutico (Corte Suprema, 1995). Estas industrias han afectado a la población de la isla a través de la diabetes, la adicción y la muerte.

España inició el sistema de plantaciones de azúcar solo dos décadas después de que colonizaron Puerto Rico. Desde 1493 hasta 1898, hasta 789 plantaciones de azúcar tenían tierras dedicadas a la agricultura comercial en toda la isla (Malone & Morton, 2021). El Tratado de París de 1898 obligó a España a ceder Puerto Rico a los EE. UU., lo que permitió a los EE. UU. nombrar a un gobernador civil bajo la Ley Foraker, Charles Herbert Allen, y colocó la isla bajo un gobierno militar. Allen era un hombre de negocios corrupto sin experiencia en prácticas y políticas gubernamentales. Recortó los gastos operativos en la isla y se negó a utilizar el superávit presupuestario para realizar inversiones esenciales en infraestructura y educación. Con los fondos adicionales, en cambio, los reorientó hacia contratos sin licitación para empresarios estadounidenses, construcción de carreteras al doble del costo, subsidios ferroviarios para plantaciones de azúcar de propiedad estadounidense (su padre era dueño de Otis Allen and Son, una empresa maderera que creó cajas y durmientes de ferrocarril vendidos, marcos de viviendas y materiales de construcción de carreteras), y altos salarios para los burócratas estadounidenses en el gobierno de la isla (Allen & McKinley, 1901). También fue catalogado como uno de los “Políticos en el Negocio de la Madera y Madera en Puerto Rico” (Biblioteca del Congreso). En el único año en que Allen fue gobernador, logró designar la mitad de los cargos del gobierno a estadounidenses visitantes (626 personas), y casi todo el Consejo Ejecutivo eran expatriados estadounidenses (Maldonado-Denis, 1972).

En 1901, Allen renunció como gobernador, huyó a Wall Street y se unió a House of Morgan (J.P. Morgan & Co.) y Guaranty Trust Company of New York como su vicepresidente. En 1907 creó el sindicato azucarero más grande del mundo en Puerto Rico, la American Sugar Refining Company (más tarde Sugar Trust). Este Trust poseía y controlaba el 98% de la capacidad de procesamiento de azúcar en los Estados Unidos. Los designados políticos de Allen en Puerto Rico le proporcionaron concesiones de tierras, subsidios fiscales, derechos de agua, servidumbres ferroviarias, ventas por ejecución hipotecaria y tarifas favorables (Tovar et al., 1971). Para 1930, Allen y sus socios bancarios convirtieron el 45% de toda la tierra cultivable en plantaciones de azúcar. Poseían el sistema postal insular, todo el ferrocarril costero y el puerto marítimo internacional de San Juan. Hoy, el sindicato se conoce como Domino Sugar.

Estas formas de modelos comerciales gubernamentales nepotistas y poco éticos han continuado hasta hoy en forma de exenciones fiscales masivas para las grandes compañías farmacéuticas (más de $ 250 mil millones entre 2017 y 2023). El gobierno de los Estados Unidos afirma que la creación de un gran refugio farmacéutico en Puerto Rico crearía empleos y apoyaría a las comunidades. Sin embargo, solo se han creado unos 7000 puestos de trabajo y muchos trabajadores se enfrentan a salarios bajos, beneficios inadecuados y mala seguridad en el lugar de trabajo. El modelo de explotación de las plantaciones de caña de azúcar se ha sintetizado en un nuevo gigante adictivo: la industria farmacéutica del imperio estadounidense (Varona, 2022).

El maestro y la esperanza de una nación

La segunda imagen, titulada El maestro y la esperanza de una nación, está inspirada en Shinō kōshō gozō no nazorae (Sufrimiento, muerte y vida efectiva: clasificación metafórica de los órganos según 4 niveles de estatus social) de Nozoki Shōshiki Rodonsai, shinō kōs hō (samurai , agricultor, artesano, comerciante) de finales del siglo XIX.

El maestro y la esperanza de una nación examina los distintos niveles de jerarquía social en el sistema de plantación caribeño-europeo. Las escenas en el estómago son resumidas por un hombre conocido como Pedro Albizu Campos, abogado puertorriqueño, activista social y nacionalista. Dirigió una huelga agrícola en toda la isla, con más de 85 asambleas sólo en 1933, lo que creó conciencia sobre las industrias de la caña de azúcar, el tabaco, la costura y el transporte. Estas asambleas o reuniones pretendían elevar los salarios de los trabajadores de la caña de azúcar de $0.45 a $1.50 por jornada de 12 horas (Villanueva, 2009). Sus esfuerzos por enseñar y alentar a otros a luchar por la libertad y la soberanía lo llevaron a vigilancia las 24 horas por parte de funcionarios del FBI, una ley mordaza y 25 años de prisión que lo llevaron a su muerte por experimentación con radiación, que se ve en su pie inflamado. Estas dosis letales de radiación causaron ronchas, quemaduras y trombosis cerebral.

Las descripciones de las escenas se pueden ver a continuación, comenzando desde el centro superior y moviéndose en el sentido de las agujas del reloj.

- Una gran plantación de cultivos de tabaco. A la derecha hay personas esclavizadas y sirvientes contratados que llevan estiércol de vaca en bolsas sobre sus cabezas. Sus hijos ayudan con las cosas pequeñas.

- Un trabajador corta el pasto para preparar la tierra para la próxima temporada de cultivos. Detrás de él yacían grandes haces de caña de azúcar.

- El dueño de una plantación/político cuenta y realiza un seguimiento de sus ganancias mientras se sienta junto a una pila de dinero.

Cornelius P. Rhoads, profesor de Patología en Harvard y personal de la Universidad y Hospital Rockefeller, se sienta a la derecha de estas escenas. Está envuelto en un kimono de calavera y tibias cruzadas, mirando una pastilla roja, que representa su vehemente apoyo a los anticonceptivos en la isla, junto con su período de seis meses en 1932 inyectando células cancerosas en el pueblo puertorriqueño. También alteró experimentalmente las dietas de sus sujetos (o, como él se refería a ellos, “animales de experimentación”) para inducir las condiciones que investigó en lugar de tratar las dolencias (Lederer, 2002). Un extracto de su carta sigue: “Ellos [los puertorriqueños] son sin duda la raza de hombres más sucia, perezosa, degenerada y ladrona que jamás ha habitado esta esfera. Te enferma habitar la misma isla con ellos. Son incluso más bajos que los italianos. Lo que necesita la isla no es trabajo de salud pública sino un maremoto o algo para exterminar totalmente a la población. Entonces podría ser habitable. He hecho todo lo posible para promover el proceso de exterminio matando a 8 y trasplantando el cáncer a varios más. Este último no ha resultado en muertes hasta el momento… La cuestión de la consideración por el bienestar de los pacientes no juega ningún papel aquí; de hecho, todos los médicos se deleitan con el abuso y la tortura de los desafortunados sujetos” (Rosenthal, 2003). Esta carta fue entregada a Pedro Albizu Campos, quien la distribuyó a nivel mundial a varios medios de comunicación. Albizu creía que Rhodes era parte de un complot más grande del gobierno de los Estados Unidos para exterminar a los puertorriqueños.

La Biblioteca de documentos de la industria y los recursos de la Colección de azúcar de IDL han agregado contexto importante y documentación de respaldo a mi investigación. Gran parte de la historia de Puerto Rico ha sido minimizada o encubierta debido a políticos corruptos e intereses especiales. Utilizar la colección japonesa de bloques de madera también ha tenido un impacto perspicaz en mi proyecto y proceso al crear imágenes accesibles para temas complejos. El próximo taller cubrirá las técnicas japonesas tradicionales de bloques de madera utilizando cinceles, tinta e impresión manual. También me referiré a los aspectos tecnológicos de este proyecto y las obras creadas a través de The Makers Lab en UCSF.