This week’s makers are Andy Chamberlin, assistant professor in the Department of Cell & Tissue Biology and Barbie Klein, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Anatomy at UCSF. Let’s take a look at their project.

Q: What did you make?

We collaborated with Jenny Tai, Makers Lab engineer, to experiment with a novel idea of replacing missing bones for the anatomy laboratory skeletons using 3D printed bones. We started this proof-of-concept project with the patella, a sesamoid bone of the knee commonly called our “kneecap”.

Q: Why did you want to make it?

The skeletons in our anatomy laboratory are extensively studied by hundreds of health professional students each year. Over time, several skeletons have required repairs and additional bones due to damage. To enhance the educational value and utility of our skeletons, we thought that supplementing them with the required bones using 3D printed ones might be feasible.

Q: What was your process?

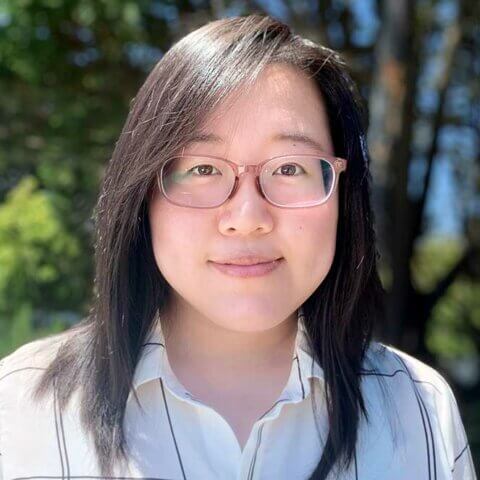

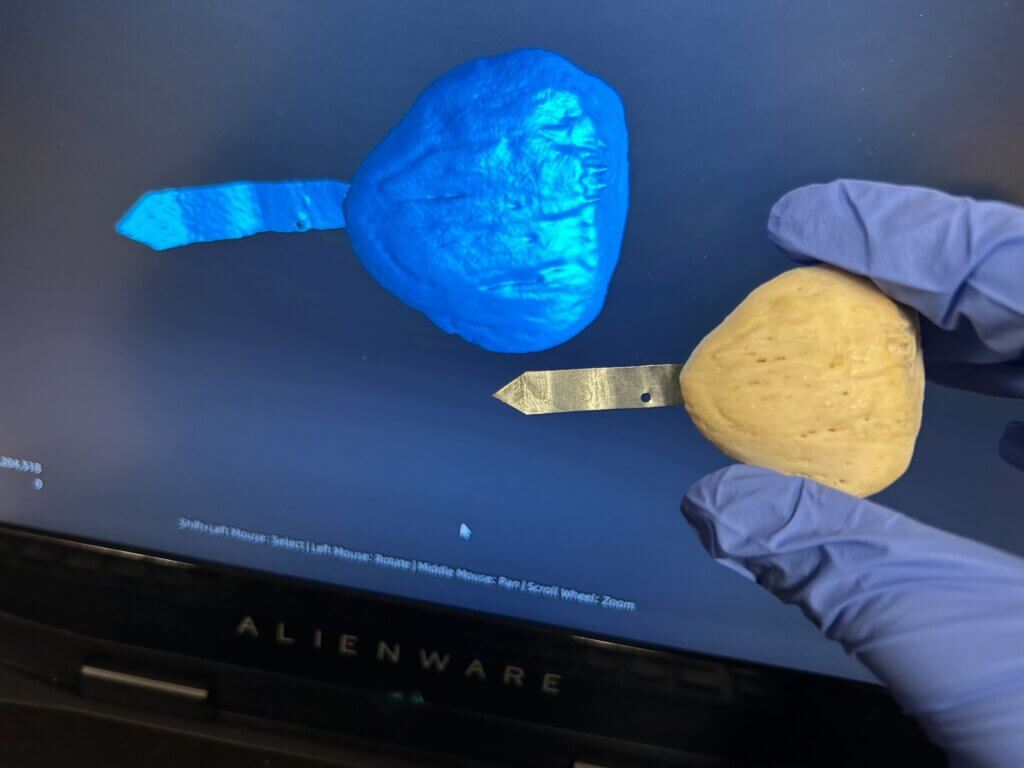

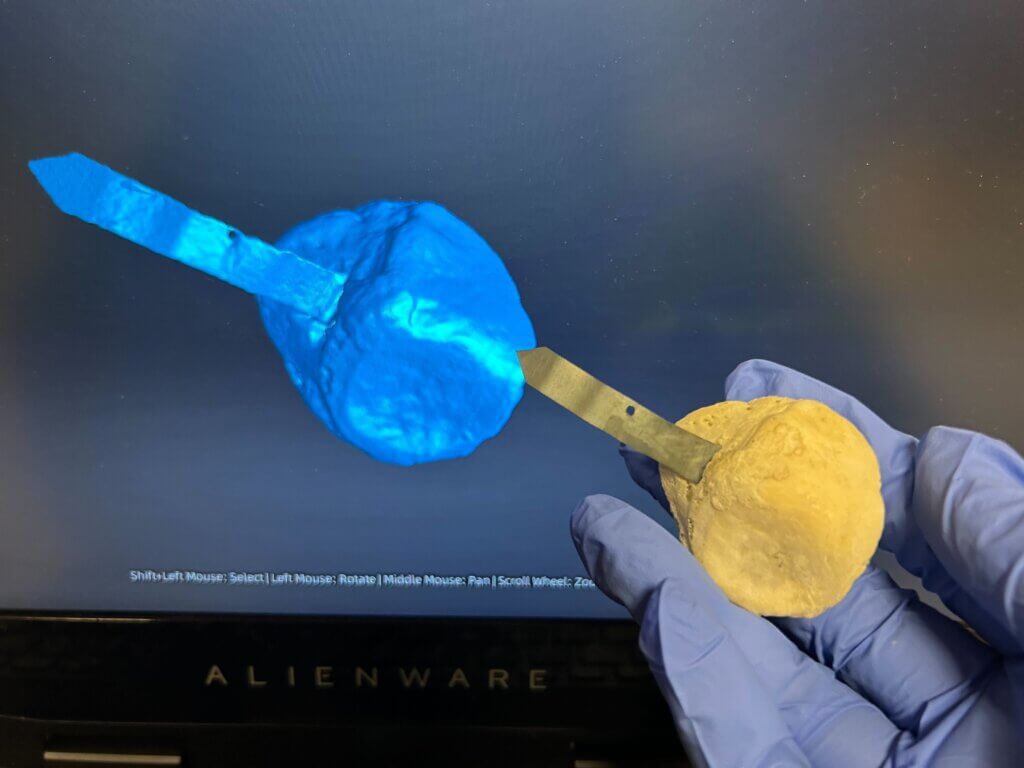

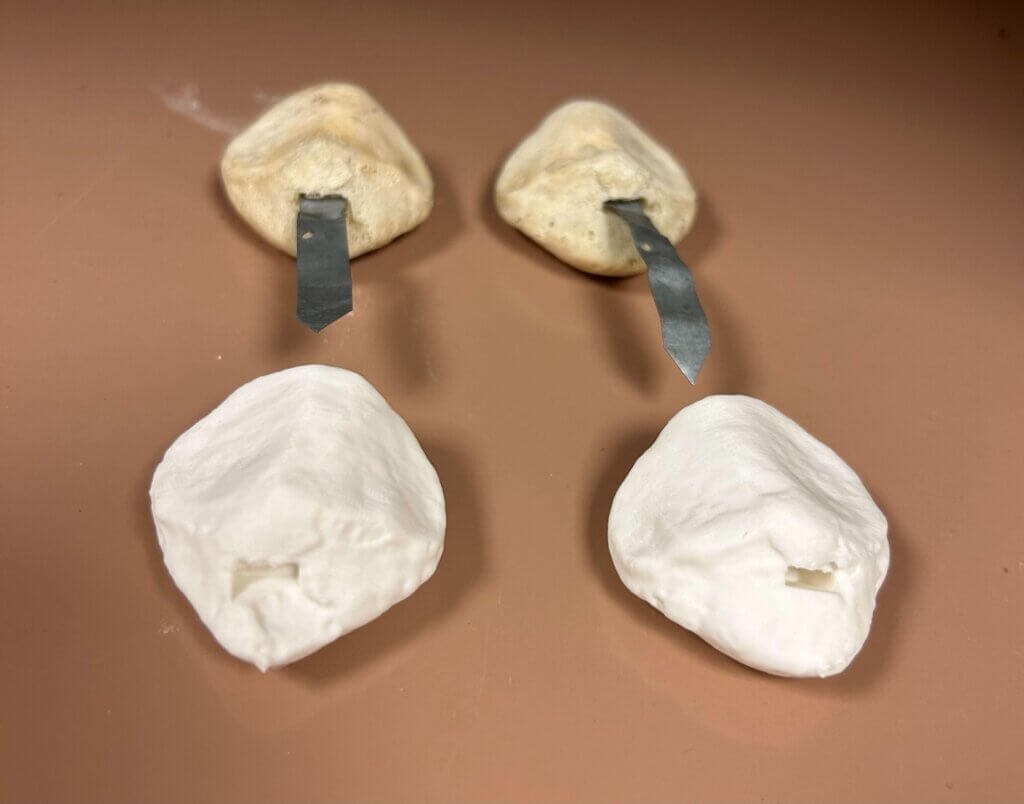

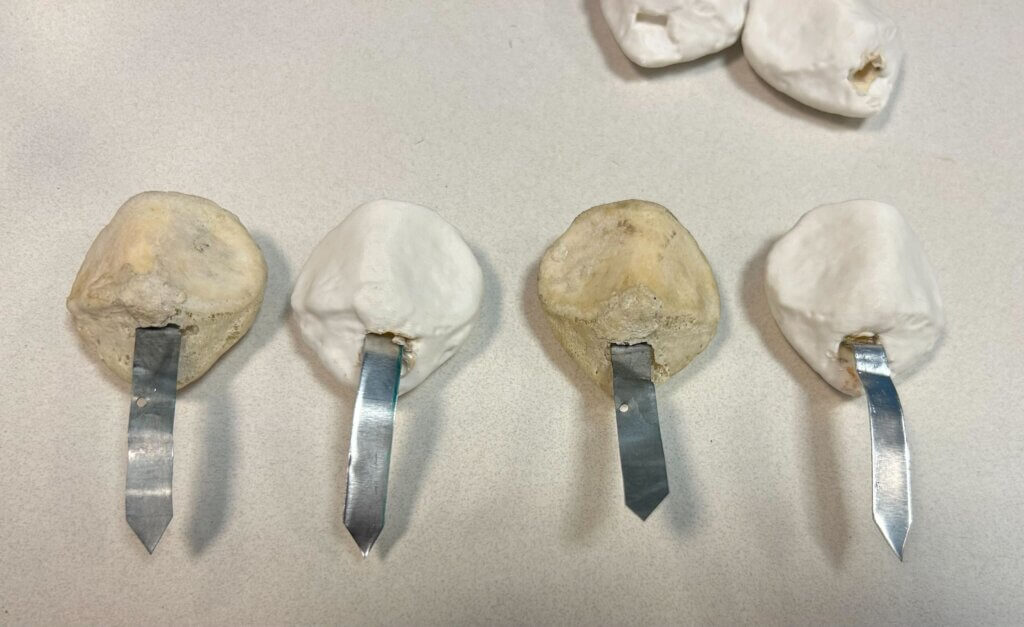

First, Jenny 3D scanned both the right and left patella to create incredibly accurate models. Next, she digitally removed the existing metal tabs from the 3D models before digitally creating a slot on the model for another metal tab. The metal tabs are required to secure the patella to the adjacent tibia. Jenny took careful measurements to ensure that the metal tabs tightly fit and were secure. To insert the metal tabs on the newly printed bones, Jenny experimented by first using a soldering iron to slightly melt the plastic but found that Bondic liquid plastic was efficient to secure it as it works well with plastic if you are able to shine the UV light on the areas needing to be bonded.

Q: What was the hardest part of the process?

Determining the best process for securing the metal tabs to the 3D printed plastic — it took some trial and error getting the aluminum to stay in place while using the soldering iron. Welding with liquid resin turned out to be a more predictable, and replicable choice.

Q: What was your favorite part of the process?

The amount of detail that the 3D scanner was able to capture in the final 3D print is astounding! The 3D printed patellae are anatomically accurate and even include small indentations from the wear of the patellar ligament across the surface of the original bony patellae.

Q: How did this help make you a better researcher/faculty?

This project was an excellent proof-of-concept and we are happy to report that it is a feasible option for missing or damaged bones. Jenny’s amazing work, creativity, and problem solving shined as the patella required some thoughtful troubleshooting.

Q: What do you want to make next?

Some skeletons are in need of phalanges (bones of our fingers and toes) and hyoid bones! Experimenting with different filament colors or post-processing with paint will help to achieve a more realistic look to the 3D printed bones.