In my role as the 2024 UCSF Library Artist in Residence, I bring a unique perspective shaped by years of training and work as a physician and a professional artist with a passion for the environment. When I applied for the residency in the spring of 2024, I intended to research Big Oil’s response to the Clean Air Act and social pressures to decrease the emission of greenhouse gases. As an artist, my most recent work concerns the relationship between fossil fuels and global warming and its adverse effects on the world’s coral reefs. I am also curious about the evolution of plastic and what can be done about the massive amounts that are accumulating on the planet.

While my research and artwork around adverse effects on coral reefs is ongoing, this artist residency offered an opportunity to view health sciences artifacts within the UCSF Archives and Special Collections. I became curious about one of the artifacts. I saw a photo of a suture set with what looked like curved needles much larger than I remembered using in the past. As a graduate of the UCSF School of Medicine (Class of 1979) and someone with firsthand experience suturing, I questioned whether these instruments were indeed much larger than the modern versions I have used. Polina Ilieva, associate university librarian for collections and university archivist, brought out the suture set and some other objects, including vintage anesthesia masks and stethoscopes to share with me during one of my visits to the UCSF Library.

These historical artifacts grabbed me in a way I hadn’t expected. Maybe it was because I had only used or seen a modern version of these instruments. I imagined how I would use an early stethoscope. I thought about the people who used these tools and put myself in their place. I imagined the settings in which they were used.

Drawing from the dozens of items I reviewed, I have selected a few to highlight for their fascinating history. I have included some background information on the artifacts for reference in this news item. It is by no means comprehensive but consists of some facets of the instrument’s history that piqued my interest. For more information, please see the references listed at the end of the article.

Stethoscope

In my pediatric residency and private practice, my stethoscope was my primary instrument. I wore it with the tubing slung around my neck like a scarf, part of my outfit. I used it for every physical examination.

The stethoscope was invented by Rene Laennec in 1816. He had a female patient with a heart problem but was reluctant to place his ear directly onto her chest, the technique for examination at the time. He recalled a trick from childhood of scratching one end of a log with a pin and having the sound transmitted to the other end of the log. He tightly rolled a piece of paper (Wilbur, 1987) – in one report, a quire, 24 sheets of paper (Bishop, 1980) – placed one end on the patient’s chest and the other in his ear and found the sound clearer than if he had examined her in the prescribed way. This method evolved into using a solid wood cylinder, then one with a hole drilled in the center.

Though ‘mediate auscultation’ (as opposed to immediate with the examiner’s ear on the patient’s chest) or listening to the sounds of the body with a stethoscope to assess various conditions, was slow to catch on, but by 1850, it was widely used in doctor’s offices. Various kinds of wood were considered: ebony and cedar, pine, cherry, mahogany, boxwood, as were pewter, brass, silver gutta percha (sap from the Palaquium tree), and even paper mâché.

Various forms of the wood cylinder evolved to an ideal shape: a stem of about 6-9” long, ½” wide with a ¼” bore, a 1-1 ½” chest piece, and a 2 ½” diameter earpiece. In 1835, wood was replaced by a cup attached to a flexible metal coil covered with silk or worsted wool yarn.

As early as 1829, there was a record of people attempting to create a binaural stethoscope. However, George Cammann of New York was credited with its invention in 1851. His design included a combination of the bell-shaped chest piece with two long tubes inspired by the monaural flexible stethoscope. By the late 1860s, the binaural stethoscope had become the standard (Wilbur, 1987).

Anesthesia mask

Before I dove into UCSF Health Sciences Artifact Collection , I was curious to see the anesthesia artifacts because that collection is highlighted on the library’s website, and my husband was an anesthesiologist. However, I found reading the history of anesthesiology as fascinating. Going back to antiquity, wine was an early intoxicant, as was the use of plants such as helleborus niger (also known as Christmas rose), dittany, opium, mandrake, hemlock, henbane, mulberry, and others. In 1776, Franz Mesmer, a German physician, was credited for “…one of nature’s mysterious motive energies” (Robinson, 1948). He theorized that there was an “animal magnetism” in the body that could be used to cure ailments.

His theories were scorned by the medical community, but by the 1830s, there was renewed interest in mesmerism and its outgrowth hypnotism. In the 1840s, the American surgeon and pharmacist Crawford Long’s ether frolics (social gatherings where participants inhaled diethyl ether for its intoxicating effects) led to the first use of ether in 1842 as an anesthetic to remove tumors from the back of a patient’s neck. However, Long did not realize the importance of this discovery and did not report it until years later when others came forward with their claims of ether as an anesthetic.

In 1844, Horace Wells, an American dentist, was the first to suggest nitrous oxide could be used to extract a tooth. A story between William Morton, an American dentist and physician, and Charles Jackson, a Harvard professor of chemistry and mineralogy, over who was the first to use ether rivals any soap opera. The controversy became lost in the urgency of the Civil War, where both sides used ether extensively on the battlefield (Robinson, 1948).

To administer ether a metal cage with gauze stretched over the metal bars was commonly used as a mask. Liquid ether was dropped onto the gauze, and the patient inhaled a combination of the gas and air. John Show, 1813-1868, was the first physician to specialize in anesthesia. He designed a mask with valves that could be swiveled according to the patient’s inhalation and exhalation (Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology).

Vaginal speculum

I had not seen a cylindrical speculum before, and that it was made of wood immediately led me to question: How was it sanitized between patients? What would it feel like as a patient? What could the examiner see?

While cylindrical, bivalve, trivalve, and quadrivalve specula were excavated at Pompeii, the use of vaginal specula was common as early as the 1500s. Joseph Récamier, considered the first gynecology specialist, re-introduced the cylindrical specula in 1801. A 5” long tin tube with a shiny surface reflected light to see the cervix, but the vaginal walls were obscured. In later years, the cylindrical specula were made of a variety of materials: ivory, glass, porcelain, wood, and Indian rubber. In 1816, he made modifications, and by 1818, a bivalve speculum was developed. More than 200 specula with various changes were made during the 1800s (Wilbur, 1987). The Fergusson speculum, originally metal, then glass, became the more favored of the cylindrical type until after World War II (Wilbur, 1987).

Breast pump

I used a manual breast pump with my own infants, so I was curious to see the one in the artifacts collection. As with the other instruments I examined, the history was as engrossing as the tool itself. I hadn’t previously thought that the centuries-long fashion of wearing corsets would have played such a large role in breastfeeding problems. It’s hard for me to imagine the power of fashion being greater than infant survival.

The history of the breast pump goes back to antiquity, for until formula was commercially produced, failure to breastfeed was life-threatening to infants. Ceramic vessels from the 6th to 5th century B.C. were found in Attica, Cypress, and Greek colonies in southern Italy. These vessels or “gutti” had a dual purpose as a breast pump and feeding bottle. In the 1400s, colostrum was considered unwholesome for the first 14 days of an infant’s life and the recommendation was that another woman should breastfeed the child and the mother be suckled by a whelp. In the 16th to the 18th centuries, women of all ranks and ages wore corsets, which caused the nipple to be flattened and caused a high incidence of inverted nipples. A sucking glass, called a “tiralette”, had the large end placed over the mother’s nipple and the long tube end sucked by the mother to draw the nipple out. Other methods included having a young, robust girl suck the nipple or applying a glass that had been heated with hot water placed over the nipple.

In 1774, a piston breast pump was applied several times a day the week before delivery. In 1782, rubber was used in breast pumps to draw the nipple out. In 1892, a double suction breast pump aided preterm infants. The teterelle biaspiratrice or “double-sucker teat” treated cracked nipples as well as fed weak infants. Milk accumulated in a glass vessel with the mother sucking a tube connected to the glass to create negative pressure. With the first power plant in 1882, electric breast pumps were standard in hospitals for decades (Obladen, 2012).

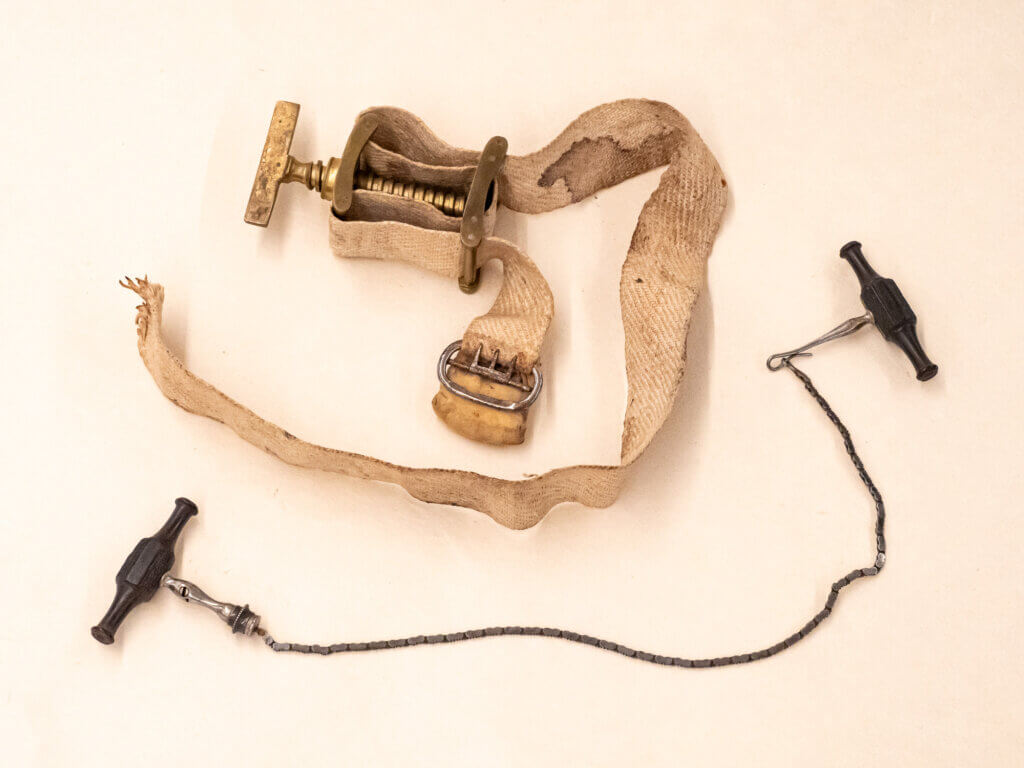

Amputation kit and tourniquet

UCSF Health Sciences Artifact Collection contains several amputation kits. What is remarkable about them, even from the thumbnails on the artifacts online database, are the saws. They’re so similar to the ones that I have in my utility room that I shuddered on first seeing them. Each kit had several knives and a tourniquet. As some of the kits are labeled from the Civil War era, my mind leaped to the battlefield and the grisly nature of the amputations that might have been performed there. What kind of sanitation was there? How was pain controlled? I’ve read accounts of how early amputations were performed, which left me queasy and glad for modern medicine, surgery, and anesthesia.

Before sterilization, wounds were likely to become infected, and even then, it was not a guarantee of survival. Sixteenth-century surgeon Ambrose, declared that “only amputation could prevent certain death from putrefaction that would creep and spread over the rest of the body” (Wilbur, 1987).

To stop blood flow during surgery, Paré used a simple ligature. A later type of tourniquet used a handle of wood twisted under the strap that encircles the limb. In 1718, Jean Louis Petit created the screw tourniquet which was the standard until the early 1900s.

Most of the knives in UCSF Health Sciences Artifact Collection are straight, though historically, there are curved knives dating back to 200 A.D. By 1775, most knives were straight. At one time the handles had a checkered texture which improved the surgeon’s grip but also trapped bacteria. Later, knife handles were made smooth to aid in sanitation. Notably, the handles I examined in the collection are checkered.

The earliest known saws were used by Egyptians more than 4,000 years ago. Ancient Greeks used copper blades, then bronze. Around 200 B.C., the Romans introduced forms of saws that were used in the coming centuries. The most popular was the tenon saw, which resembles an ordinary carpenter’s saw that is used today. The bow saw resembles our modern hack saw. By the 1500s the bow saw was heavily embellished with wood, bone, or ivory handles, and the blade tightened with a screw device. In the late 1700s the tenon blade became more popular as it was sturdier and reinforced with a steel spine. The late 1700s also saw the Gigi-Haertel saw with chain links, which gave this saw the advantage of cutting in any direction (Wilbur, 1987).

Suture set

This is the first image from UCSF Health Sciences Artifact Collection that attracted my attention. I was drawn to the size of the curved needles. Could they really be that large? On inspection, they did indeed appear much larger than the needles I remember using in my training. What was most fascinating was that the hole intended for suturing was located near the tip of the needle. At the opposite end is a bolt designed to fit into a forceps-like clamp. How could such an instrument be used?

After looking at it for a time, I imagined that the needle would be threaded with suture and then clamped onto the forceps. A tail of suture would be left on the near side of the incision. The pointed end would enter the near side and rotate to come out on the other side of the incision. The suture would be withdrawn from the needle eye and the needle then retracing its path back through the large hole it created. This would leave suture ends on both sides of the wound which can be tied. Suture ends were cut, and the needle was rethreaded for the next stitch.

Unfortunately, after an extensive search I was unable to find another example of the clamp and curved needle set, nor an example of a curved needle with a hole at its sharp end.

I was fortunate to meet with Wen Shen, MD, MA, an endocrine surgeon at UCSF who has a master’s in history of medicine and teaches a mini-course for medical students on the history of surgery. He had never seen this tool either but agreed with my assessment as to how it was used. I thank him for this corroboration.

What the artifacts have taught me

After months of thinking about the vintage artifacts in UCSF Health Sciences Artifact Collection, I wondered why I was so passionately drawn to these tools. When I left pediatrics to study art, I left behind the tools of my practice — stethoscope, otoscope, tongue depressor, reflex hammer — mere objects. Why would I now see these vintage tools with such intense interest? As an artist who works primarily with materials and forms imbued with meaning, such as plastic discards, tea bags, and the hexagon shape, I look further into my artist materials to discover what else they tell me. I look beyond the surface of my materials for connections to concepts that resonate with me. With brewed teabags, I find physical warmth, intimacy, and thrift. With plastic, I ask myself, how did this come to be in our world? How does it touch human lives? What will happen to it when it’s no longer useful? For the hexagon forms, I studied the ways they are depicted in nature, from the molecular structures to a vast geographic scale.

In my artwork, I communicate connections that are not superficially obvious and challenge viewers to discover these connections. I know that experiencing these items from UCSF Health Sciences Artifact Collection will sharpen my understanding of new materials for future artworks.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express gratitude to the UCSF Library Artist in Residence team, including Polina Ilieva, associate university librarian for collections and UCSF archivist, and Dylan Romero, library operations analyst. I would also like to thank Sean McClelland, UCSF Library’s manager of technology innovations for photographing and editing images of the artifacts; Lupe Samano, records and accessioning archivist for her assistance with researching the health sciences artifacts collection; Wen Shen, MD, MA, for his assessment of the suture set; and Jessica Crosby, UCSF Library outreach and marketing coordinator.

All items highlighted in this article come from UCSF Health Sciences Artifact Collection.

Works cited

Bishop, P. (1980). Evolution of the stethoscope. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Volume 73.

Obladen, M. J.Perinat (2012). Guttus, tiralatte and teterelle: a history of breast pumps. Med. (40) 669-675.

Robinson, Victor (1948). Victory over Pain: A History of Anesthesia. Henry Shuman, Inc.

Wilbur, C. Keith (1971). Antique Medical Instruments. Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.

Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology https://www.woodlibrarymuseum.org/museum/snow-mask/