This week’s maker is Nina Patel, UCSF Head and Neck Surgery Prendergast research fellow. Let’s take a look at what they made.

Q: What did you make?

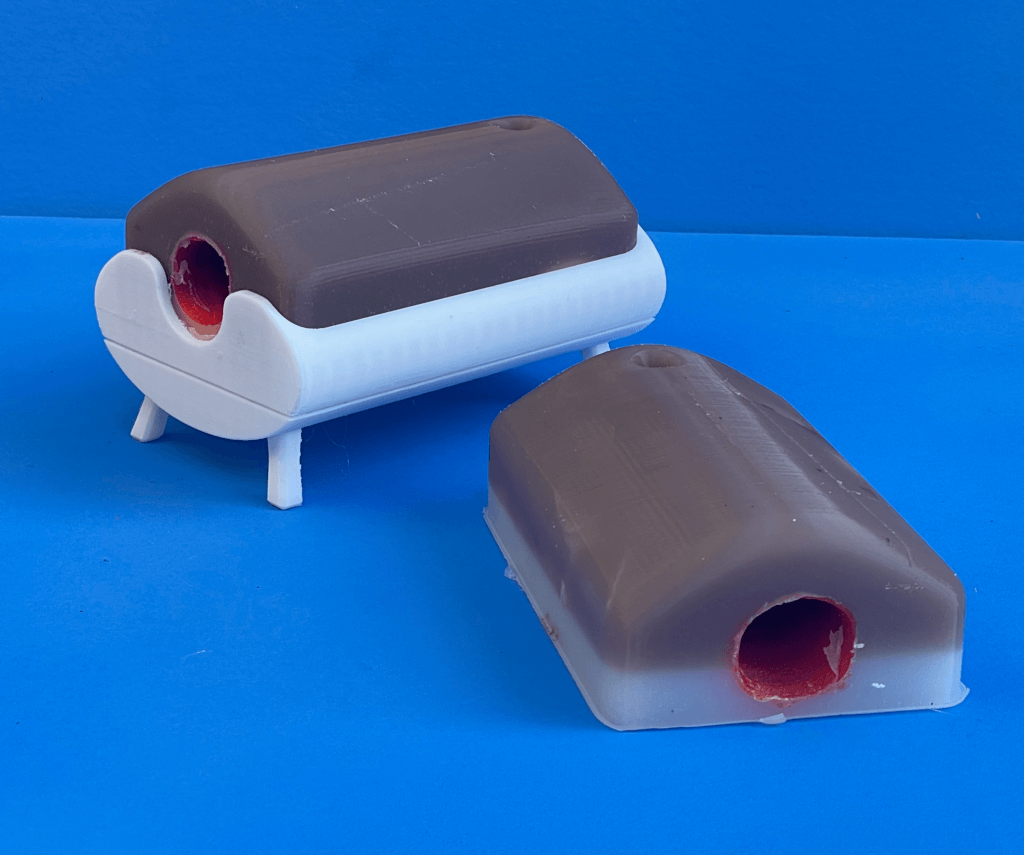

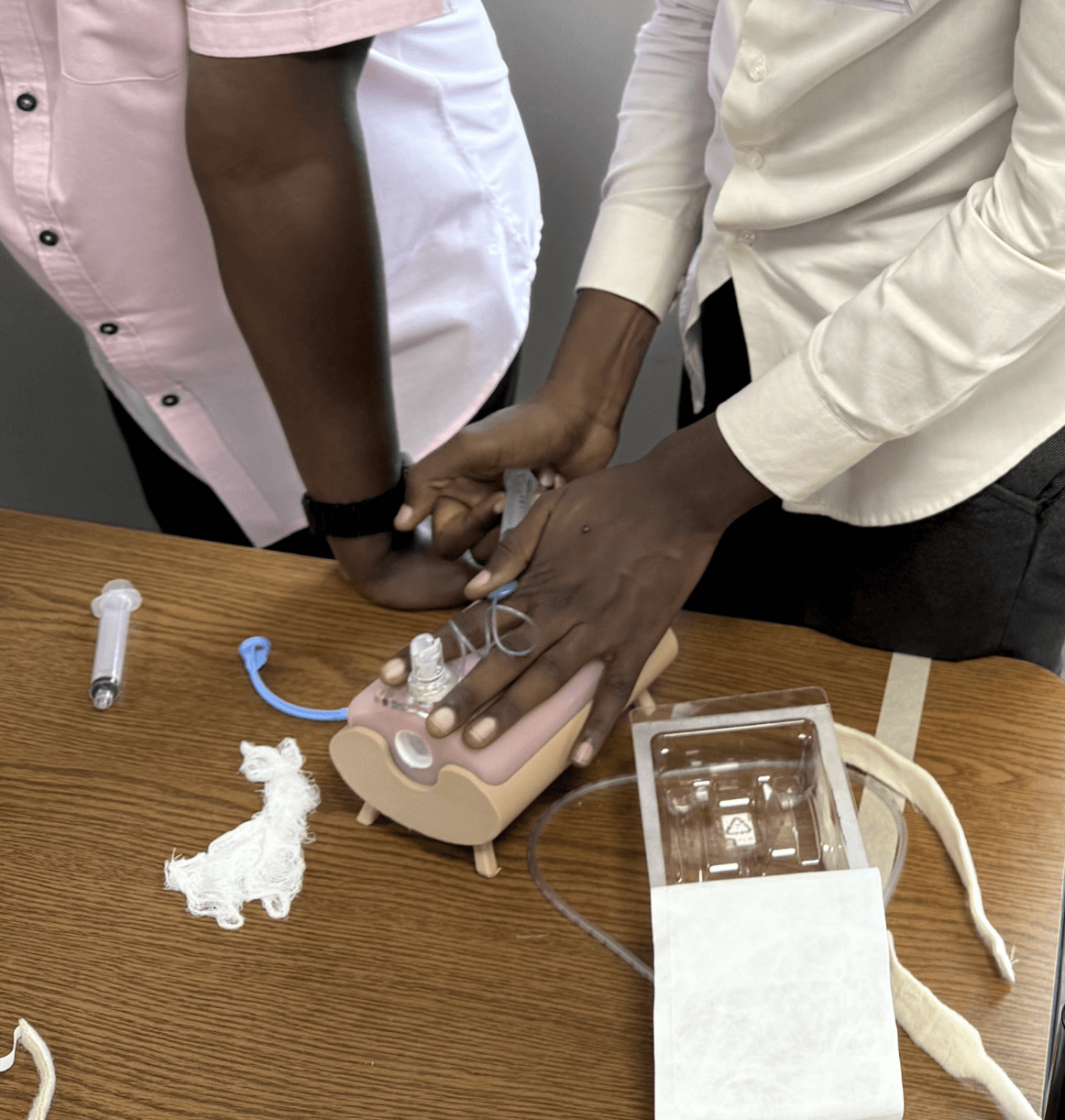

We created a 3D-printed tracheostomy simulation model designed for hands-on airway management training in low-resource settings. The model replicates the anatomy relevant to tracheostomy (neck and trachea) care and was used as part of a simulation boot camp in Kigali, Rwanda, to train general practitioners (GPs) in relevant and life-saving procedures.

Q: Why did you want to make it?

Tracheostomy care is a critical but often under-trained skill for general practitioners in many parts of the world, especially where specialist support is limited. After hearing feedback from Rwandan providers about low confidence when managing tracheostomies, a surgical procedure where an opening is made in the neck and trachea and a tracheostomy tube is placed to help a person breathe, our team wanted to create an anatomically accurate, low-cost, sustainable model that could be used to improve provider training and ultimately patient safety.

Q: What was your process?

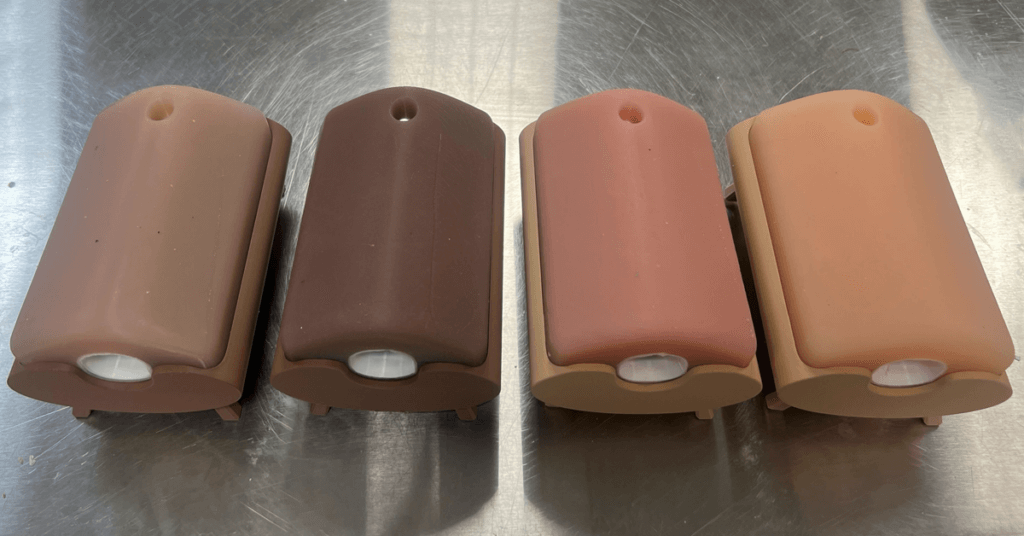

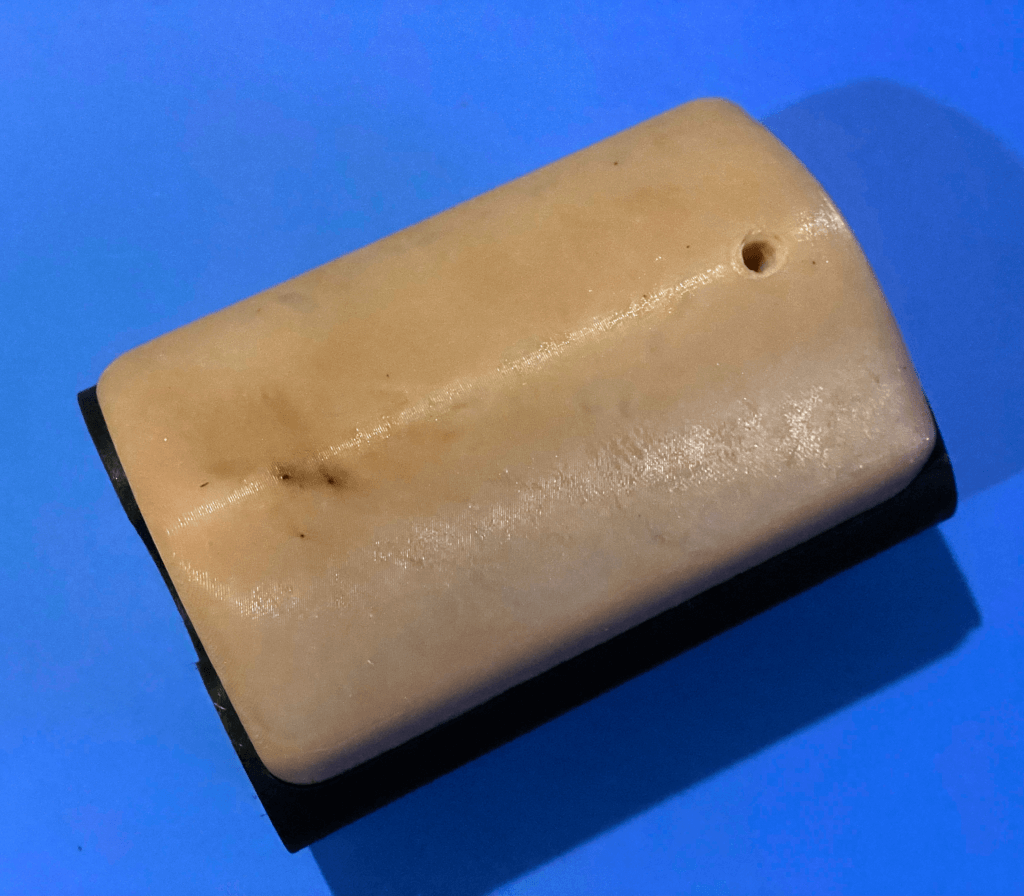

The process began with researching airway anatomy and reviewing available open-source models. With Scott Drapeau, the designer at the Makers Lab, we used 3D modeling software (Blender) to create, adapt and customize a tracheostomy model that would be both durable and anatomically relevant. Scott made a few different prototypes with a focus on materials testing and optimizing print settings for flexibility and strength until we settled on a version that worked for our purposes. Scott then shared the files and assembly instructions with Joshua Cobbett, the Makers Lab innovation technology specialist, so he could produce a total of five units. The working prototypes were then used in a multi-station simulation training session in Kigali, Rwanda for over 50 regional GPs.

Q: What was the hardest part of the process?

Balancing anatomical accuracy with material availability and durability was the most challenging part. We wanted the model to feel realistic during procedures like suctioning and tube replacement, while keeping it low-cost and portable enough for use in training programs across the region.

Q: What was your favorite part of the process?

Seeing the model in action during the boot camp was incredibly rewarding. Watching general practitioners build confidence and competence through hands-on practice showcased the importance of this collaborative effort. Their feedback helped to further validate the model’s relevance and impact.

Q: What do you want to make next?

Next, I’d love to expand this project by developing a modular simulation toolkit for ear, nose, and throat (ENT) care more broadly, including models for nasal packing, foreign body removal, and flexible laryngoscopy. Laryngoscopy is a procedure where a light and a lens are used see the back of the throat, larynx, and vocal cords. The goal is to create a suite of low-cost, high-impact training tools that can be used to scale ENT education in underserved settings.

As part of our work with the tracheostomy simulation model, we also collected detailed data from otolaryngologists and general practitioners on several key aspects: the model’s anatomical accuracy, relevance to clinical practice, perceived cost-effectiveness, and its ability to improve confidence, comfort, and hands-on skill. Feedback was gathered through structured pre- and post-surveys, and the insights gained are now guiding refinements to enhance the model’s realism, durability, and educational value.

We’re excited to use this feedback to further optimize the existing design and implement improved versions in future trainings—not only in Rwanda, but also in Tanzania. Our goal is to expand access to high-quality, simulation-based education for general practitioners, nursing staff, trainees, and other front-line health professionals who play a vital role in airway management and emergency ENT care.

This is just the beginning of a broader vision to make practical, hands-on ENT education more accessible in low-resource settings.